How do you think about it?

Abstract

Two subjects are consistently banned at family gatherings: politics and religion. This is because everyone else is wrong many of us feel very strongly about those matters, generally because we are directly affected or have a lot of self-esteem riding on “being right”.

As with anything so widely cared about, we generate an almost endless amount of political discourse, and everyone, no matter their qualifications, wants to express themselves. There is so much political discourse that we can often hear people commenting on the discourse itself rather than the politics it conveys, this is what we want to study here.

How emotionally do we express our politics, and is it affected by our proximity to them? Is the question we aim to answer.

Methods

In our data story we focus on how groups of people feel about certain issues.

To test our hypothesis we use the quotebank dataset, which we filter by issue, then we run sentiment analysis on every issue, keeping years separate, finally we use Wikidata to associate a person with each quote.

Sentiment analysis

In fine, this allows us to observe sentiments by month, issue, country, gender, and religion. Then we can observe whether the tone of discourse evolves over time, if specific groups have different attitudes, and what is the overall mood of one issue compared to another. By splitting quotes into neutral, negative and positive we achieve an idea of discourse tone.

We selected four highly controversial topics in the english-speaking world:

Abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. When steps are taken to achieve that effect, it is an induced abortion, but the word abortion generally refers to those procedures. Without intervention, it is generally known as miscarriage. The debate over the ethics of abortion is old, Aristotle makes ethical comments on the matter in 350BCE within his Politics treatise. The discussion is likely to be as old as abortion itself, which dates back to at least early antiquity, but we lack sources on the debate at the time.

Since the middle of the twentieth century, most of the western world authorizes abortions in one fashion or another, in the United States the debate is still very much ongoing, with stances ranging from treating the procedure as a form of murder to keeping it as a right for all citizens while guaranteeing its easy and safe access.

Climate change

Climate change refers to the current warming of global temperatures caused by human activity. Scientifically, the matter is quite cut and dry. It is happening, and if nothing is done to widely mitigate the changes it brings, the consequences will be dire. Politically, this is a different matter, where many deny the science openly, others minimize its impact, some offer little in the way of change, and others yet propose radical solutions. What must be done, which countries must do it, should anything be done at all, etc etc this is a complex issue with no political consensus.

The debate has been raging since the eighties, and is unlikely to wane as we start experiencing the consequences and urgency increases.

Gender equality

This one hardly needs introducing. Gender equality. Particularly women’s rights, is a fight present worldwide through feminism. In the western world, especially in the United States and United kingdom, voting rights for women were secured in the first half of the twentieth century amongst a wealth of other individual rights. Despite this, equality has yet to be achieved in many places. One current struggle in the US focuses on sexual harassment and violence against woman, exemplified by the Me Too movement.

Gun control

Simply put, the United States of America allows most of its citizens to privately own firearms. Individual States and cities may further restrict said rights. Overall one third of americans own guns. The United States are famously the flagship of school shooting, having multiple times the incidence of entire continents. This is widely attributed to the easy access of guns within the country, as is the prevalence of gun crime.

This issue is extremely divisive in the context of the United States, as the right to bear arms is the second amendment of the United States constitution, the country’s founding legal document. Many americans consider almost completely unrestricted firearm access to be the cornerstone of their way of life.

The tone of discourse

Comparing issues

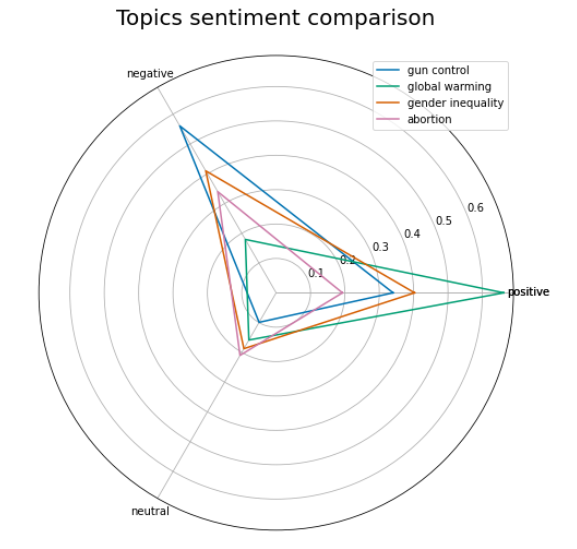

Is emotivity equal throughout the discourse, or is that dependant on subject? To answer this we look at sentiment by matter over our four chosen.

We see that three issues are distributed quite negatively, and the fourth one is much more positive, this does not indicate that the discourse is predominantly negative, as the dataset does not represent total prevalence of discourse, and especially since global warming has 60% more quotes that the three other matters put together.

Those emotional scores, or compound scores indicate that the discourse is predominantly emotional, and that neutral statements are a minority(16.4%). This is relatively unsurprising as our quotes are in english, and mostly american, originating from a country with a high intensity of political theatre with a thoroughly polarized public. The neutral chunk of our corpus could easily be factual explanations of the situation.Peter Atkins, an eminent chemist stated : ‘Temperatures go up every year, so we got to try and mitigate that.’ And while that is not explicitly in favour of climate change, it is a far cry from the denialism usually adopted by one side of the conversation.

This raises an important point, our work is not an evaluation of opinions, but of emotionality. There are ways to talk positively and negatively about most issues, and as such our work bears little to no correlation towards the positions of the quotees.

Comparing people

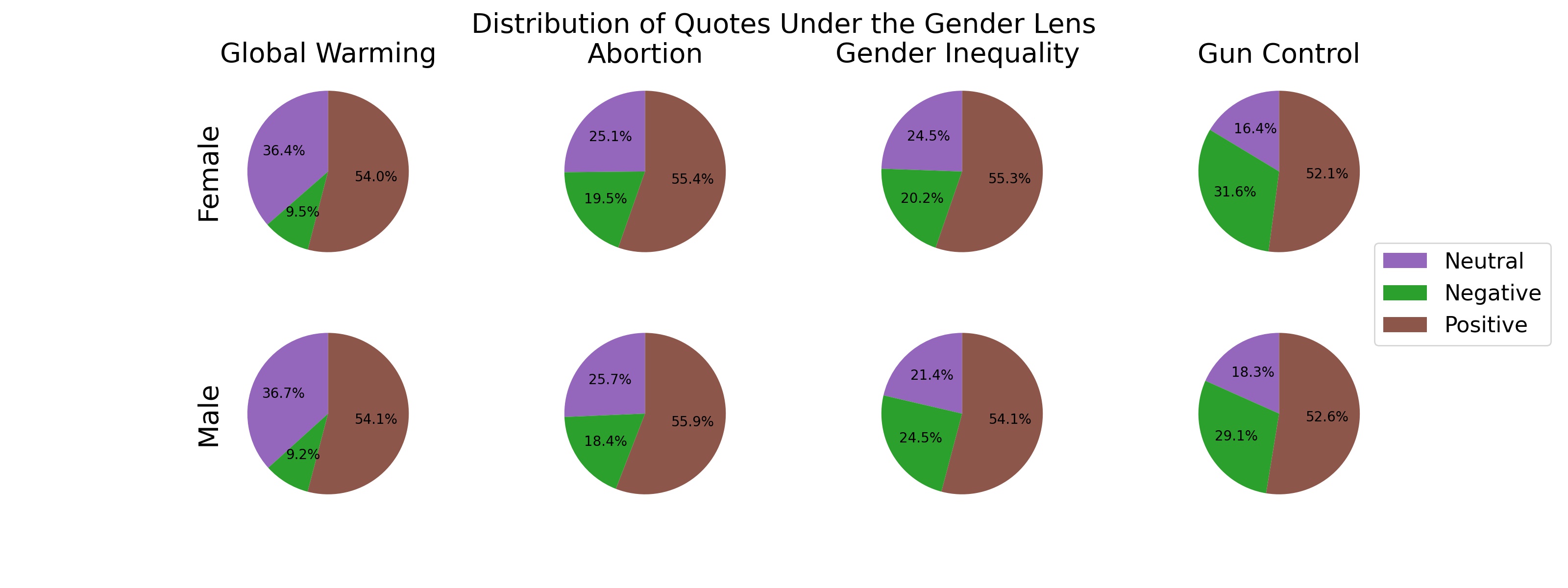

As noted above, each topic tends to have their own level of emotionality, but therein a new question arises, are we all as emotional, or does that depend on our proximity to the matter? It seems obvious to us that germans, having no guns, would hardly care about gun control, while women, often given the short end of the stick and usually the beneficiaries of abortion, might be more sensitive to those issues.

Looking at a gender distribution of emotions, we note that three subjects are similar, with women being slightly less neutral every time, but not by much. The interesting thing here is the jump in negativity on the gender equality issue. This is interesting, as we see that neither matter nor social group is a good predictor alone, some groups are especially sensitive on some issues.

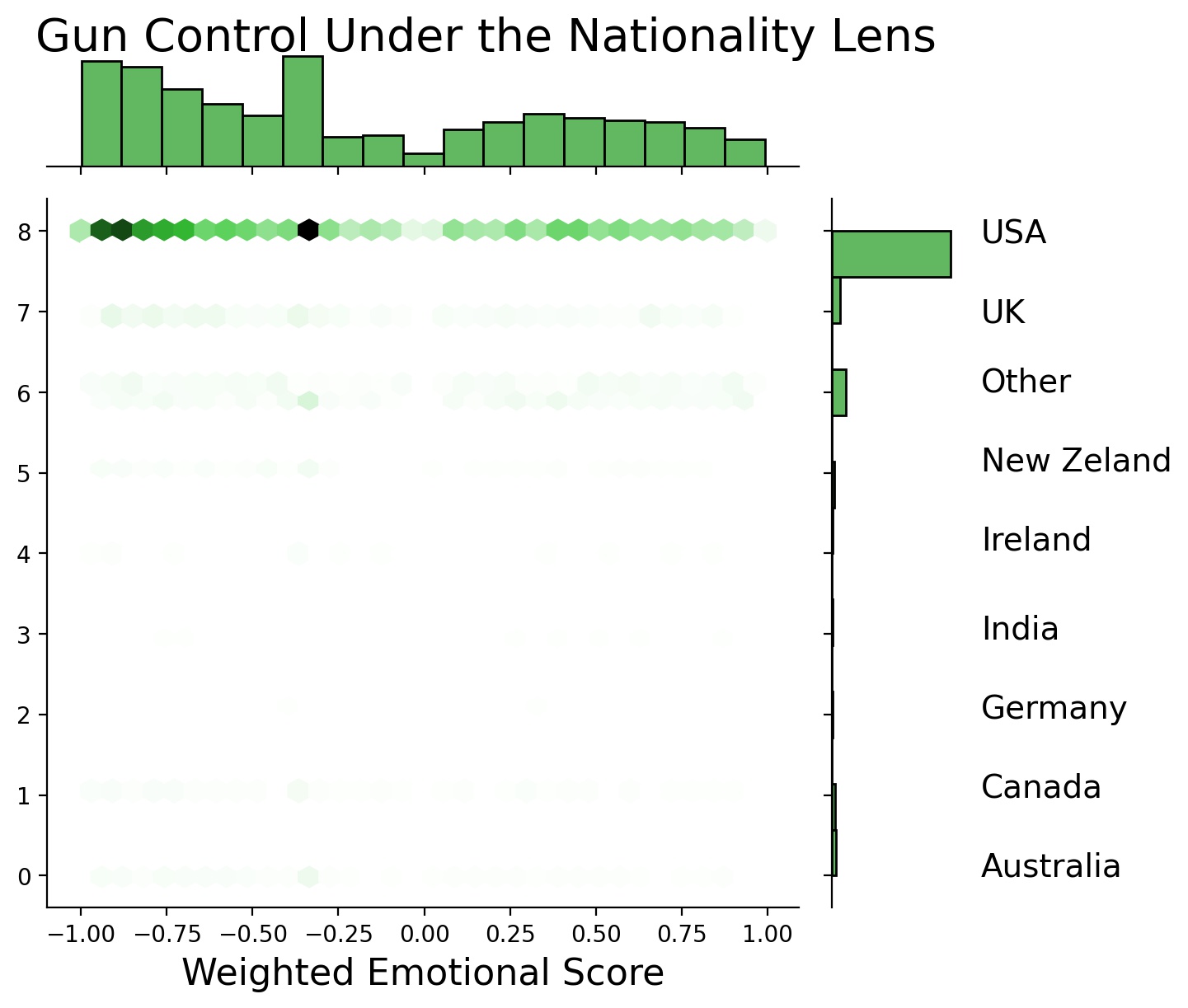

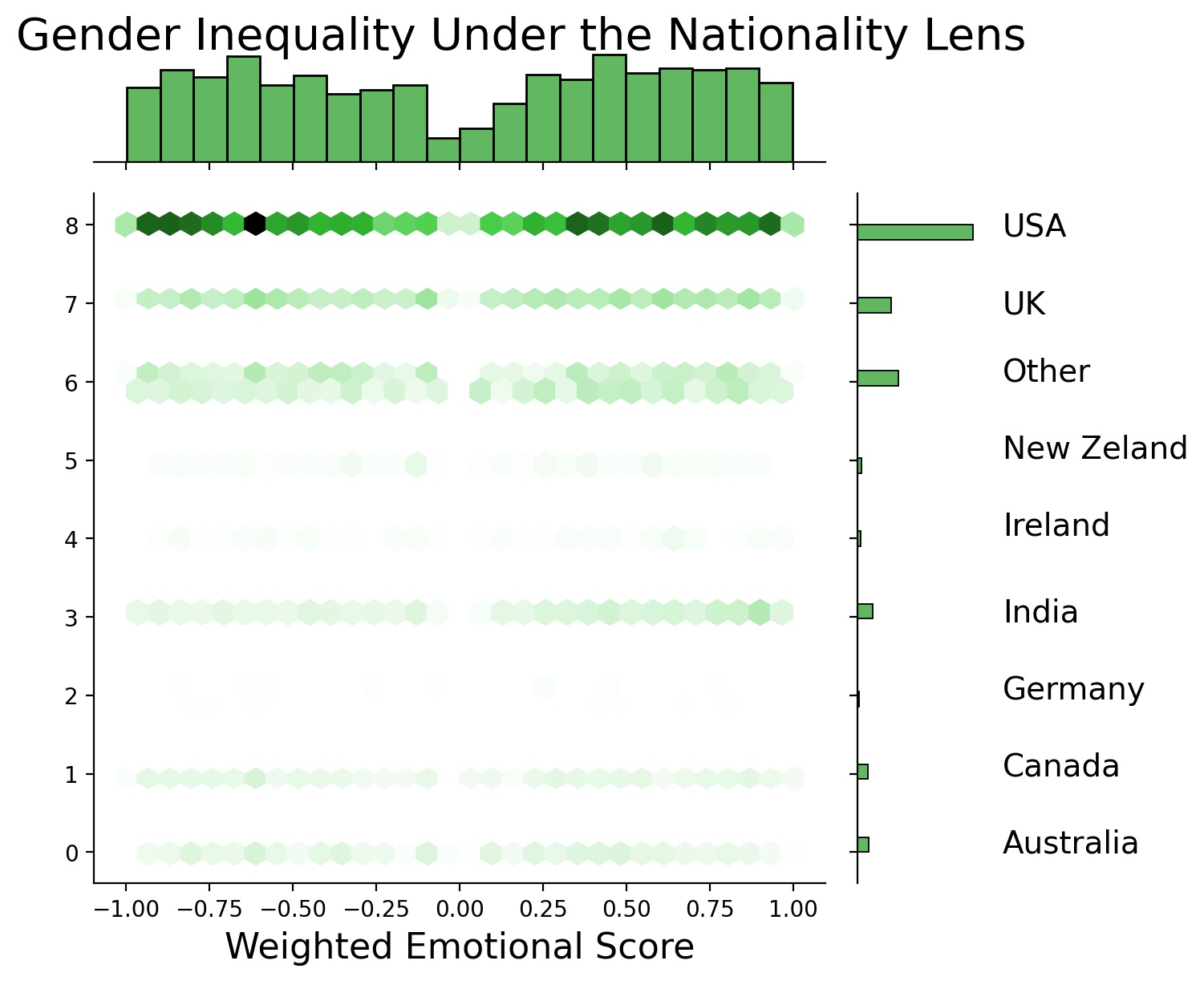

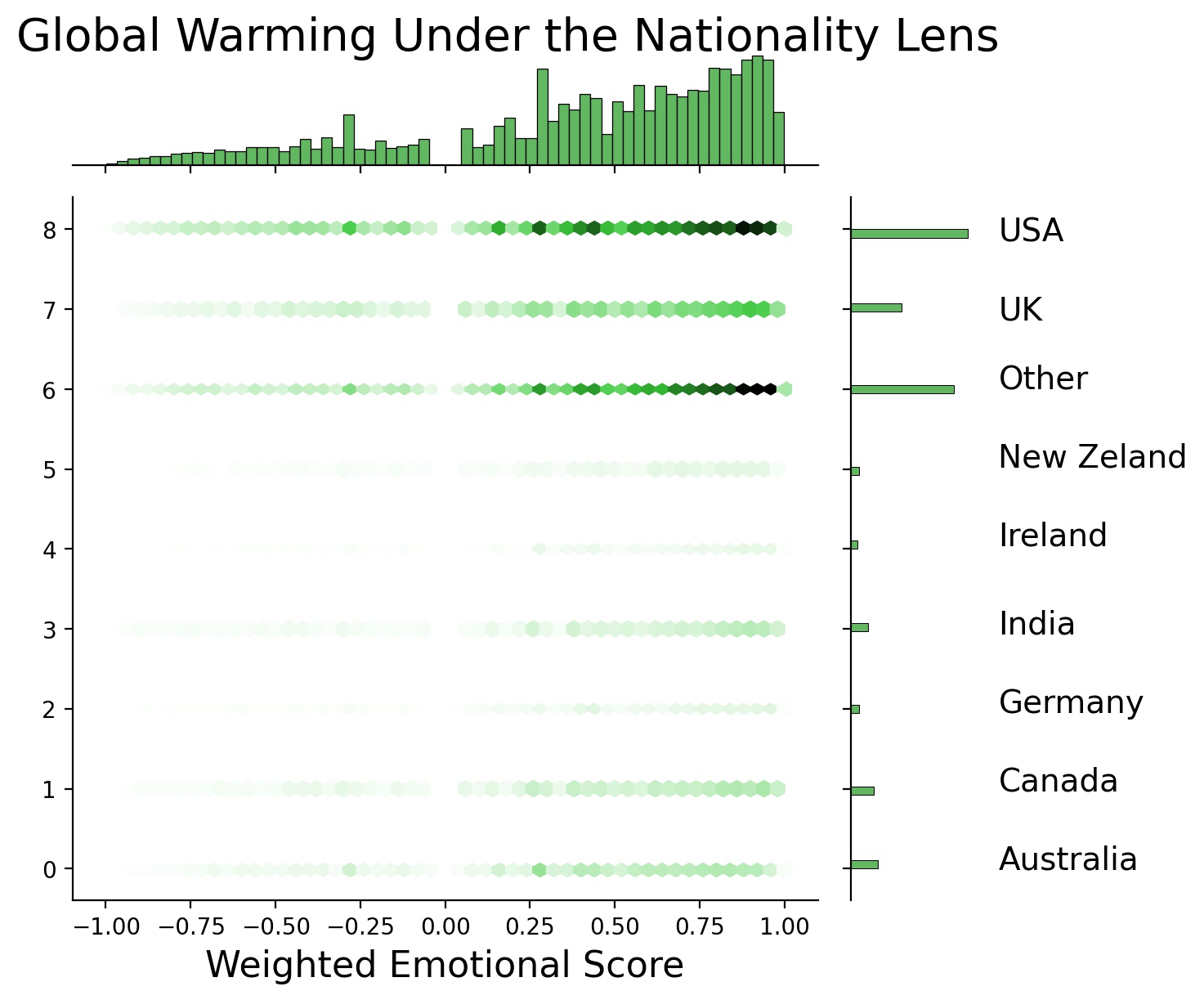

Another grouping one might be tempted to use is nationality, but this falls a little short, as we would need to operate over multiple languages with datasets obtained through similar methodologies to make a fair international assessment. Yet, there is an angle of analysis we can consider and that is comparing different extractions of data, by simply noting differences between different aspects of the dataset, we manage to negate some sources of bias. An easy example would be to compare countries in respect to gun control, climate change, and gender equality:

Here we observe that global warming is a subject with international english attention, while gun control is thoroughly american, this does not signify that other countries do not have discussions about gun control, but it does tell us that these are either expressed internally or absent. A quick media survey of german media will quickly show that it is the second for that country. As such, this is mostly an indicator of how international climate change is.

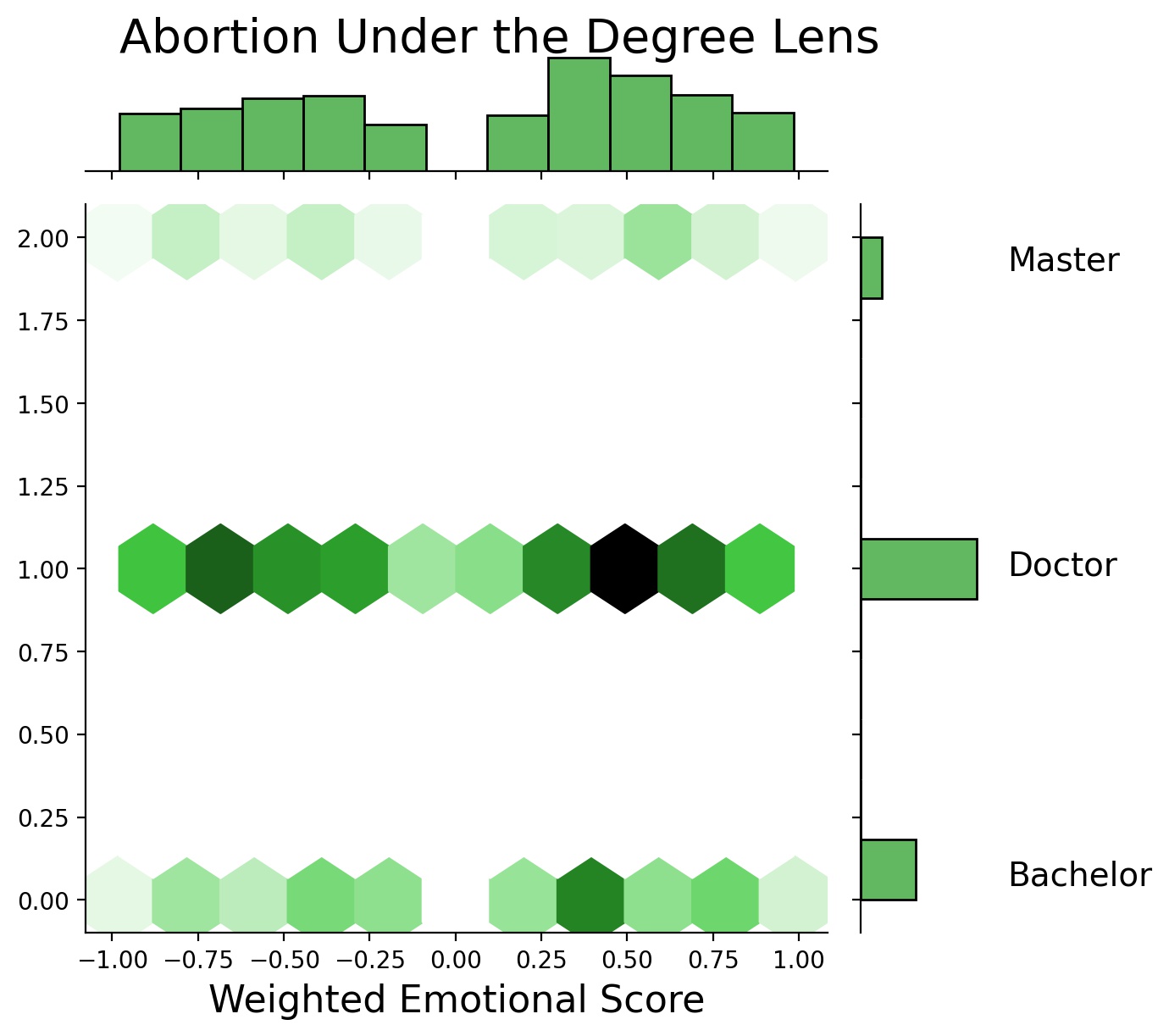

Our last social group is opinion by education. The data in itself is not too interesting, apart from one point.

The amount of Doctor’s relative to other college degrees is overwhelming. We can only deduce that this is means they are more listened to in public discourse. The truly interesting divide would be between those who did and did not go to college, as the differences in opinion between those groups are marked, but the data is sadly lacking.

Comparing epochs

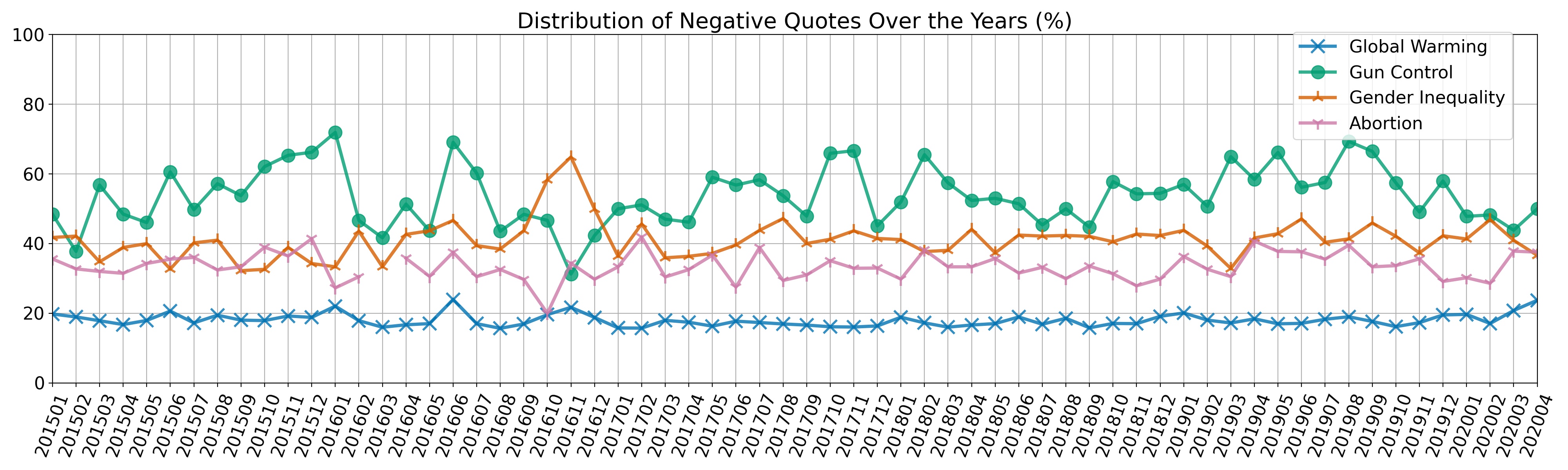

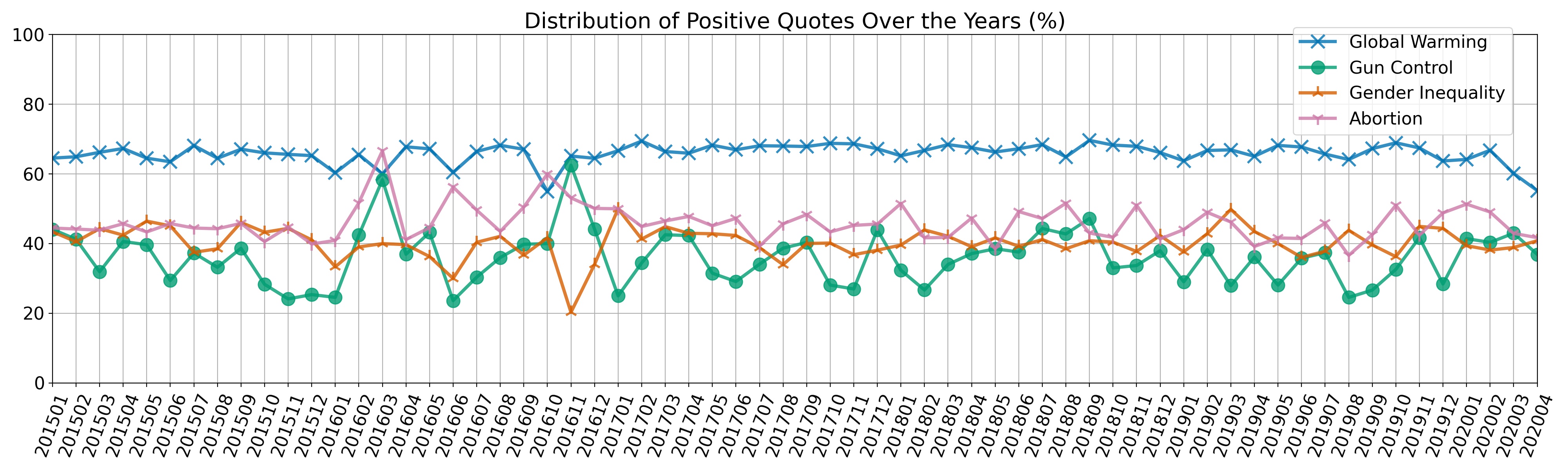

Finally, we look at sentiment over time:

We next study the sentiments of the issues over time. We look at how strongly people’s opinions vary over the months and years. Clearly during certain months talk about an issue is more passionate. This could be caused by some event. For instance, after mass shootings occur, more people are likely to be more emotive on gun control. On the 12th of June 2016, a mass shooting occurred in Orlando Florida. This clearly sparked the conversation.

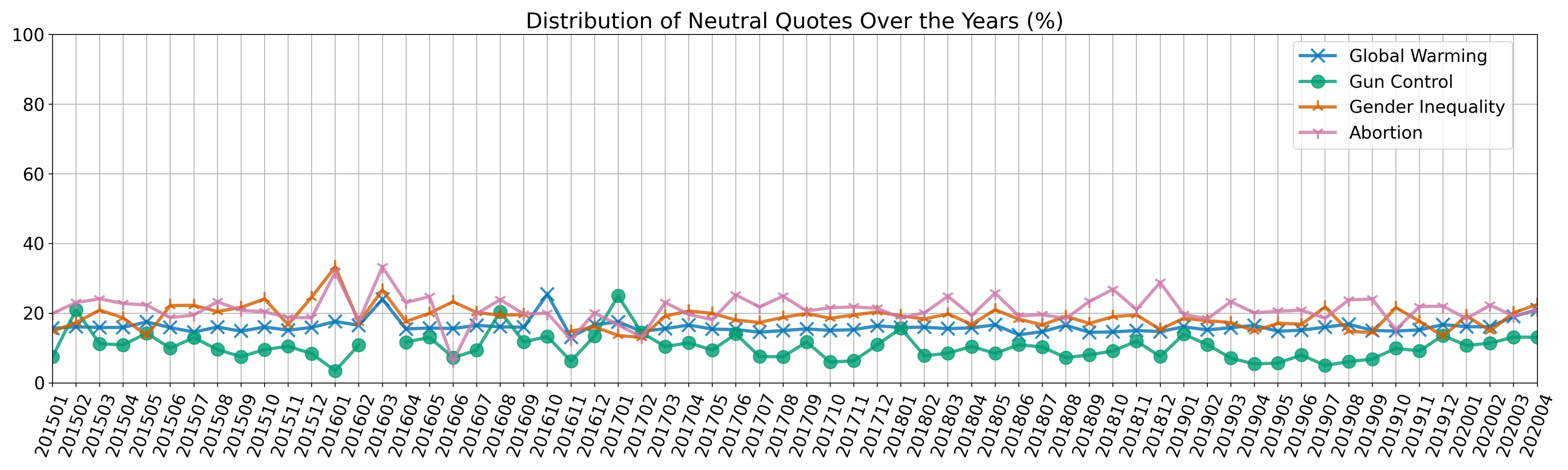

We can note other events have caused peaks of one emotion or another. Neutral quotes tend to stay a small, stable minority. Most of the variance in emotional quotes is between both emotional states.

An interesting observation is that the emotivity of discourse seems to evolve very slowly over time, wherein many complain that the election of Donald Trump poisoned public discourse, our data indicates that this might be more of a bias than anything.

Conclusion

To conclude, we have proven our initial hypothesis, some groups feel more strongly on certain matters than others, but those interactions are not universal, and most of the discourse analysed here does not stray far from its baseline emotionality.

Though, or dataset is limited to english quotes, and quotes are only a window of total discourse, as such the findings here are not set in stone.

As a last word, our team would like to specify that the science of climate change is clear, it exists and is happening, and the feminist struggle for the equality of all genders is an admirable endeavour.

Authors:

Antoine Bachmann, antoine.bachmann@epfl.ch

Elsa Rizk, elsa.rizk@epfl.ch

Tikhon Parshikov , tikhon.parshikov@epfl.ch